ESM Welcomes College MatchPoint to the Team! Learn More

The demographic shift predicted for over a decade has arrived, with fewer high school graduates affecting college admissions nationwide. As institutions adapt to these changes, students are rethinking the value of a degree. This article explores the trends shaping higher education’s future and what they mean for families and schools alike.

For over a decade, the college admissions world has been mulling over the census data revealing a looming demographic cliff. Birth rates declined around the time of 2008’s Great Recession, setting in motion a future decrease in high school grads, which is finally upon us. Initial discussions, principally led by the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education at national and regional conferences, were academic in nature. Now, the issue is imminent and affecting colleges, big and small, public and private. When I attended this year’s annual conference of the National Association for College Admission Counseling, the tone of the conversations regarding the shortfall of students had shifted. Some colleges and universities are contemplating budget cuts, layoffs, and the elimination of academic departments, while others are facing more existential threats.

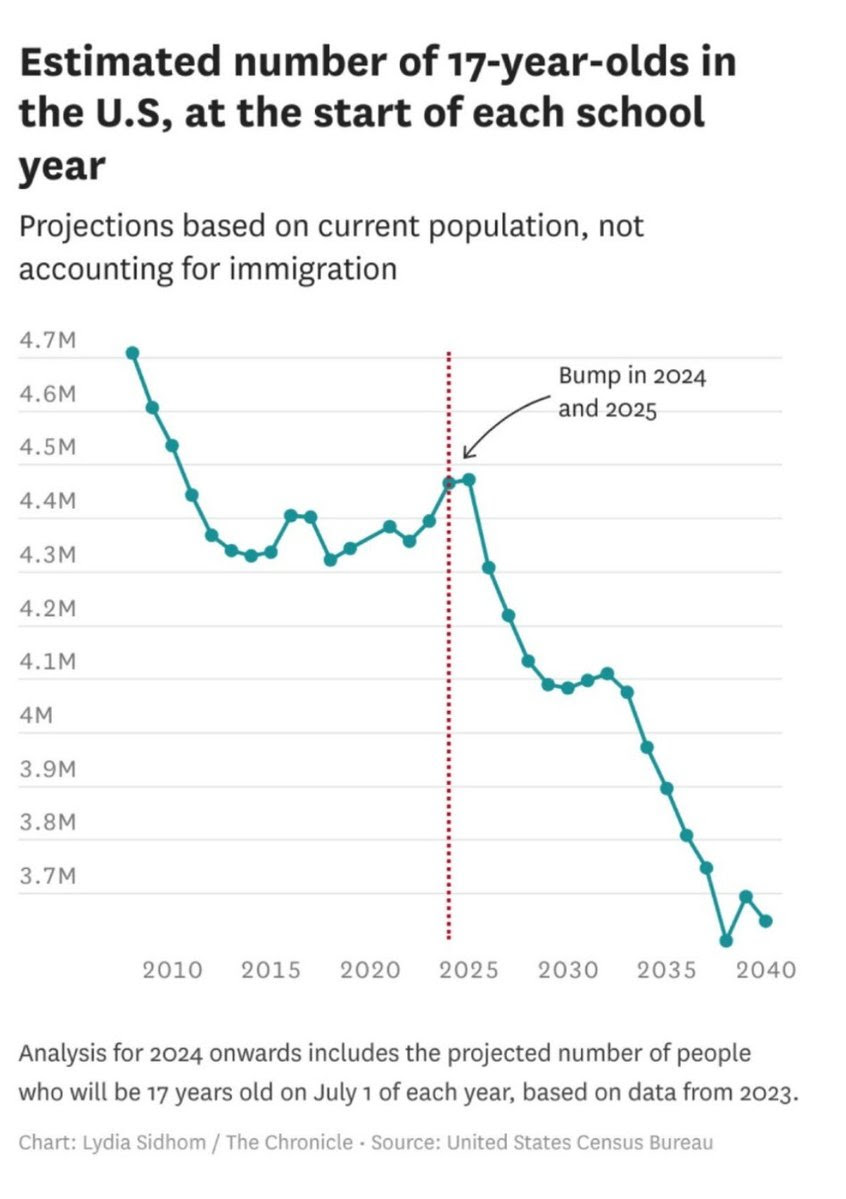

To understand the challenges coming to higher education, consider this graph showing the impending decline in high school grads, already set in motion.

This data is eye-popping. That’s a lot of missing kids in the educational pipeline! These future classes are already set: the high school grads of 2038 are currently in kindergarten, and we can measure the decrease in class size from previous years. While the US will certainly pick up some students through immigration, the vast majority of immigrants coming into the country are not going to be the full-payers that colleges will need to balance their books. And these immigrants will certainly not be distributed evenly around the country; some of the areas hardest hit by demographic decline are receiving the lowest levels of net immigration. We may also be able to offset some of the decline by attracting international students to matriculate to US schools, but the global market for higher education is becoming increasingly competitive, and our pricing is significantly higher than in most other countries.

As with most industrialized nations, the United States is facing a net decrease in births and an aging population. The replacement rate at which a population is stable is 2.1 births per woman. Some countries, particularly in Asia, are experiencing fertility rates well below replacement, which will have enormous societal consequences. Consider South Korea’s fertility rate of .9, Singapore’s 1.1, China’s 1.2, and Japan’s 1.3. Play this out a few generations and a country will face very real economic challenges. Today Japan’s universities are already struggling with its rapidly shrinking student base.

We are not in the dire straits of these countries, but our national birth rate is down to 1.7, with very meaningful differences across states. While Texas has a birth rate of 1.84 and Alaska 1.89, just below replacement, Vermont has a fertility rate of 1.35 and New Hampshire 1.41. It’s no surprise that some of the states losing population, particularly in the northeast and midwest, are using significant financial incentives, cash and student-loan forgiveness, to lure students to stay and settle in-state.

What makes the differential birth rates across states so impactful to attendance patterns at local colleges and universities is that most higher ed. students stay close to home. According to educational researcher Jon Boeckenstedt, “56.2 percent of students at public four-year colleges attend an institution less than an hour’s drive away from home, and nearly 70 percent attend within two hours.” So immigration booms in the Southeast are not going to help struggling colleges in Vermont.

In addition to declining birthrates, there has been a significant reappraisal of the value of a 4-year college degree among college-age students. Since the pandemic, many students have left the education sector without matriculating to higher education. With a relatively tight job market, many young people are heading directly into the workforce without attempting college. Additionally, tax-payers and governments have been shifting funds away from higher education. Apart from the brief reprieve from Covid-funds, states have been defunding colleges for decades. We are not prioritizing post-secondary education, and are leaving it to the institutions to fend for themselves.

The most highly selective and financially well-endowed colleges in the country are less concerned by these demographic and behavioral trends. They have powerful internationally recognized brands and prestige, which will endure any demographic downturn and ensure they can fill their classes for decades to come. However, that cohort of schools makes up a small fraction of the 2,600-plus 4-year colleges in the US.

As pandemic funds have now been depleted, many smaller, less selective colleges are currently struggling to make ends meet. The smaller private colleges and regional publics are struggling the most. Many are cutting programs, consolidating operations and campuses, selling off real estate, and even closing. Vox reported on the incredible shrinking future of college. Similarly, the Hechinger Report noted that we are seeing a decline in colleges at the pace of one college failure every week. When a college fails, it is incredibly disruptive to current students and demoralizing for alums. The very risk of a college closing will push students to consider more financially stable educational options, accelerating the flight from struggling institutions. Nobody wants to even consider that their college could be shuttered in several years, and some might consider the bond ratings of a smaller college as important as location, aid awards, and majors offered.

Given this changing landscape in higher education, we can expect that students will become more pragmatic as they evaluate the landscape of academic opportunities arrayed before them, and the net investments they are willing to make. Students applying to smaller schools with declining attendance will need to closely consider the financial stability and viability of each institution to which they are considering applying.

When the local population declines, competition among colleges to attract students, particularly more affluent and full-pay students, will intensify. Struggling institutions begin to remove any and all barriers to entry to attempt to lure students to apply and matriculate. Fast applications, automatic admission, increased use of merit awards: whatever schools can do to keep their doors open will be on the table. As a father of two children in preschool, I wonder what the admissions world will be in 2038-2040. Will it be easier for my kids to get in? Likely not at the top tier of schools, but potentially a step or two down. When supply and demand shifts, market forces will shift the behaviors of buyers and sellers. There’s a very good chance there will be nowhere near 2,600 4-year colleges by 2040, but with a smaller population, and economic forces driving consolidation, that may not be a bad thing.

In the new world of education with intensified competitive dynamics, and obvious winners and losers, expect to see more pragmatic students/consumers. Education is and has always been a business. As we cross over the demographic cliff and see its downstream effects, I imagine the emergence of a savvier consumer looking more closely at the net transaction: what I’m giving, and what I’m getting in exchange. This transformation is already underway as students are looking beyond college to the job market and considering how their 4-year degree will set them up for success in the next phase of life. This is driving changes in how students approach colleges, what majors they select, and how they view this significant financial investment.

The winners in this new world will likely be the colleges with the most established national and international reputations. These will be the safest picks, and savvy students will direct their energies toward those institutions with the most clear and stable return on investment. The public flagships will remain highly competitive as will the prestigious private schools. Students will continue to have many options for admission, highly selective and less selective, in a world with far fewer than 2,600 colleges. While this next decade will be a highly stressful time for many colleges, students surveying the admissions landscape can have confidence that they’ll be able to find an academic home long after we have crossed over the demographic cliff.