The digital ACT is coming, and we’re gaining clarity on the new format, content tweaks, and what it means for students. With a practice test released, registrations open, and new insights from ACT researchers, this article breaks down the latest updates to help you prepare for this exam's evolution in 2025.

In December, ACT, Inc. released the first practice test for the Core ACT, opened up registrations for the spring ACT tests, and conducted a webinar outlining the validity studies conducted last year on this new, shorter test. We are getting a clearer picture of this test, how it has changed, how many seats are available this spring, and the implications for students.

We have known the basic form, structure, and timing of the new ACT for several months: the test is shorter, Science is optional, and students have more time per question. Last month, ACT, Inc. released a full practice test, available here. This test was very familiar to us, as it is an adaptation of a previously released test form, 24MC1, one of the official tests in the ACT big red book. The fact that the practice test is a mere modification of a pre-existing test form speaks volumes. This is not a radical redesign of the ACT. The content changes are modest.

ACT has previously announced that the same concepts on the current test would be tested on the new version, ensuring that old prep materials remain useful. There are only a few minor tweaks. For example, every English section will have one passage that is argumentative, and the Science section is adding more questions that require outside knowledge. Apart from these changes, the new test will feel very familiar.

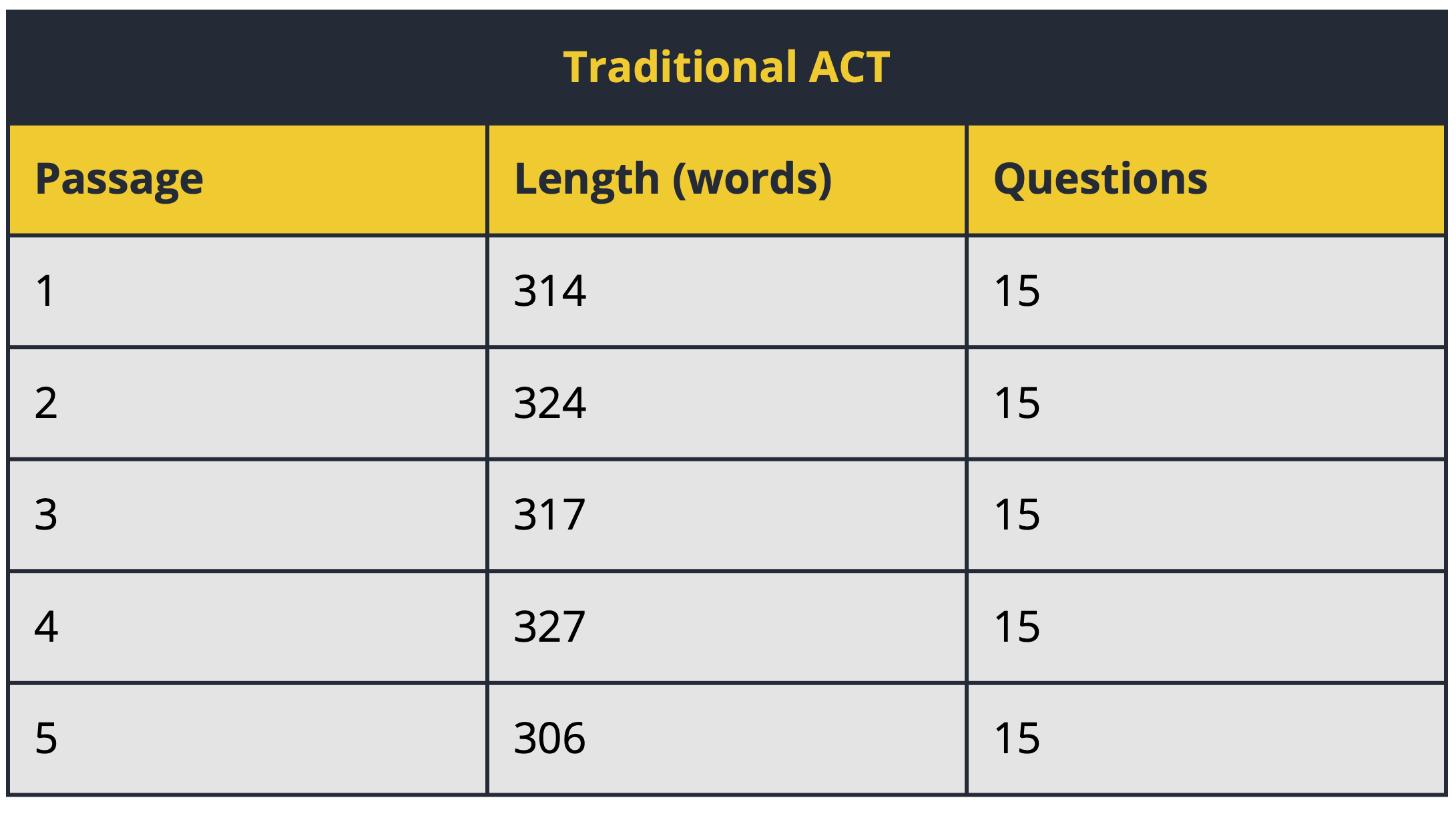

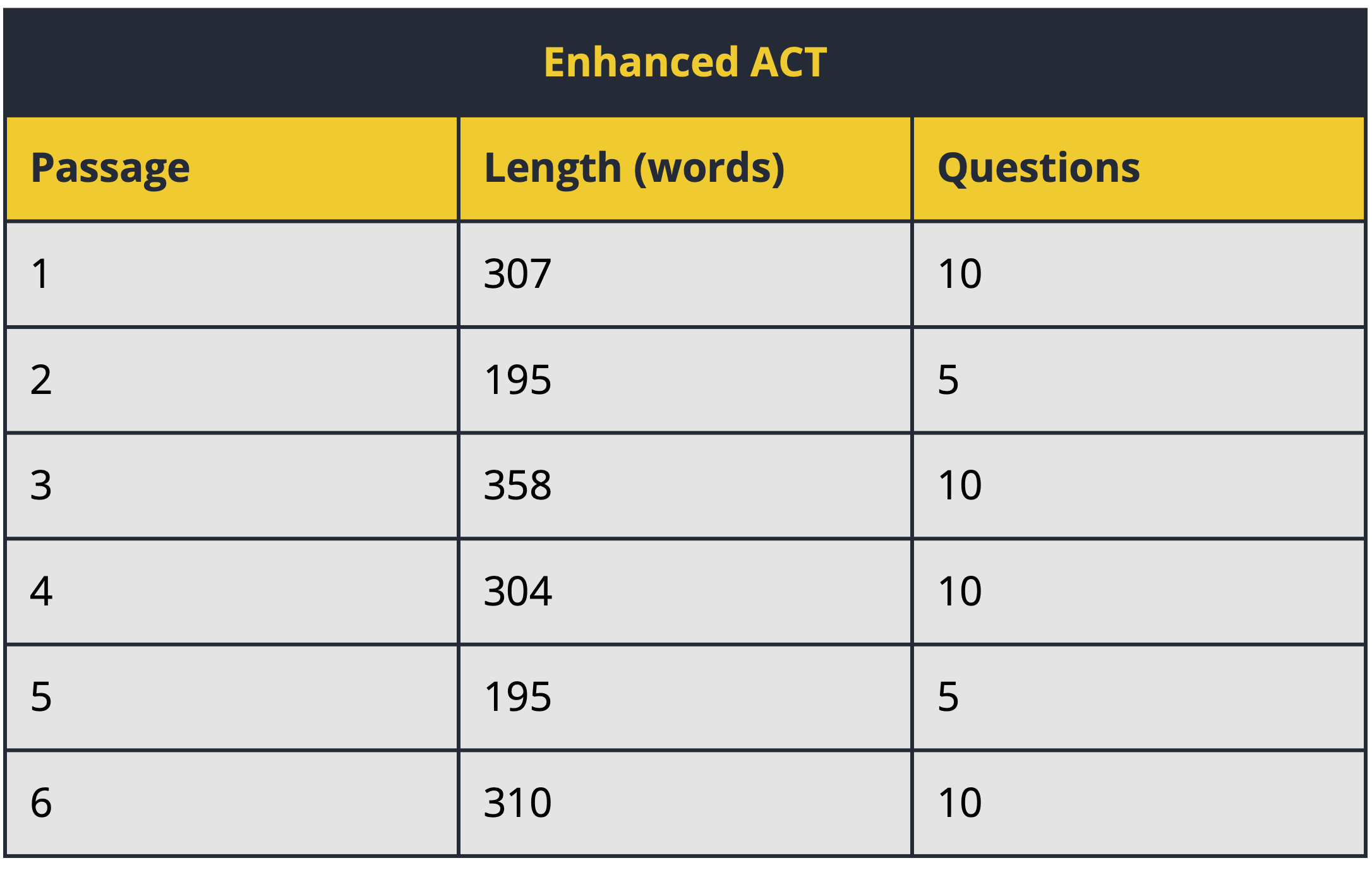

The length of the passages in the English, Reading, and Science sections has shifted, and now we have a clearer sense of the new format.

English has shifted from the traditional format of five, 15-question passages

to a format with short- and longer-form passages and fewer questions per passage. On the first practice test, the English section contains four standard-length passages (around 300 words, 10 questions apiece) and two shorter passages (under 200 words, 5 questions each).

The Reading section revealed few structural changes, apart from the shift from 10 questions per passage down to 9 questions. The Science section included 1 additional passage but fewer questions per passage.

The test writers culled easy and hard items to arrive at the shortened test form. The average difficulty level of the remaining questions seems consistent with previous tests. Given that the experimental items are now embedded in the test, leading to a reduction in operational items, the scaled scores will be based on relatively fewer test items. Further, students will have more time to solve fewer questions without a commensurate increase in difficulty level. If a student has more time without more difficulty, it’s natural to assume that raw scores, derived from adding the number of correct responses, should increase. More students missing fewer items could lead to a more punishing scoring scale at the top of the scoring distribution. Until we can access the results from the April digital ACT administration or a new official study guide with scoring tables, we will be in the dark regarding raw to scaled scoring and the impact of missing individual items on the test.

While individual-level scoring data is lacking, we have heard from the ACT researchers and test writers regarding the reliability and validity of the shortened test form. In July, 7,600 students participated in a “linking study” of the Classic and Core ACT tests. In December, ACT researchers delivered a webinar, currently available on demand, which revealed the findings from the investigation. While small differences in raw score distributions between the shorter and longer forms were found, the researchers achieved nearly identical scaled score distributions after statistically linking the two tests. Hopefully this forecasts relative stability in scoring when students move from the current to the Core test.

The ACT researchers also found that including or excluding the Science section should not shift composite scores beyond a single point on the ACT: this may encourage colleges to accept Core ACT scores without requiring the Science section. As expected, a shorter test did lead to an increase in the standard error of measurement and a modest drop in reliability, a natural trade-off in test design. Reliability remains high enough, and the confirmatory factor analysis revealed that the test remains valid and continues to assess the foundational academic concepts it is designed to assess.

The ACT is using a platform called ACT Gateway that is built off of the familiar Pearson TestNav interface, in use since 2019 for all international ACT test takers. As a platform, TestNav lacks some of the functionality of the College Board’s Bluebook testing interface. Bluebook has superior features including the ability to annotate on the screen, the visual overview of the test section, and the embedded Desmos calculator (which ACT, Inc. hopes to add to Gateway eventually).

Further, the ACT’s digital platform, unlike the Bluebook platform, requires a constant, stable internet connection for the duration of the test. This could pose a problem for test centers that may experience latency and lag issues when their networks are stressed. A slowdown during testing due to bandwidth limitations would obviously adversely affect test-takers. ACT has posted its technical requirements here, outlining the bandwidth needed to successfully run ACT Gateway.

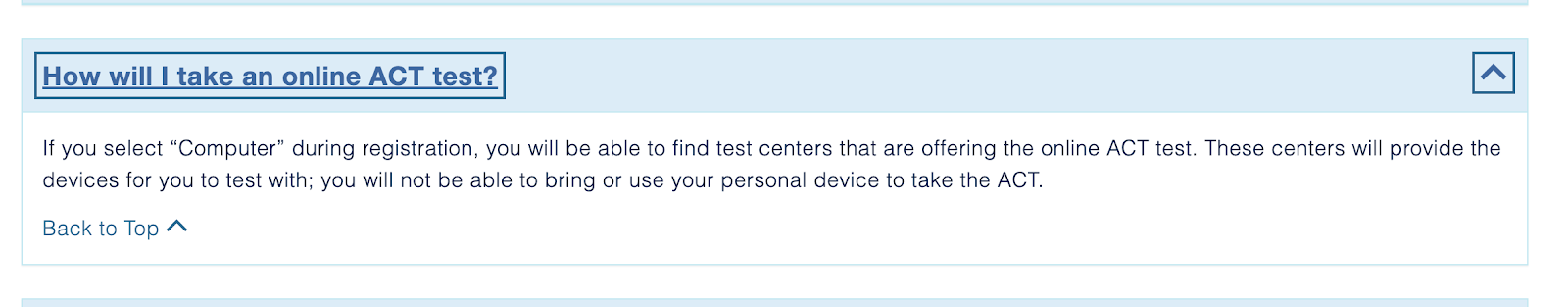

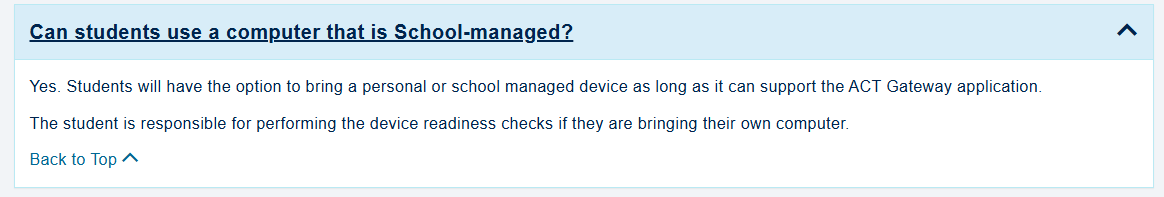

The ACT has advised that students could bring their own devices—Chromebooks or Windows computers, but no Macs or tablets—to take the digital ACT. Allowing students to bring their devices removes the burden on schools to provide all the needed hardware. However, the ACT website has not been consistent with its messages regarding the implementation of this BYOD policy.

In the ACT online questions page, the ACT website indicates that students will not be able to bring their own devices for digital testing:

But the Bring Your Own Device Resource page advises that students can bring their own devices.

We certainly hope that students will be able to practice on their own computers and bring them to the testing centers as they can with the SAT. Students may need to clarify the policies by contacting individual test centers.

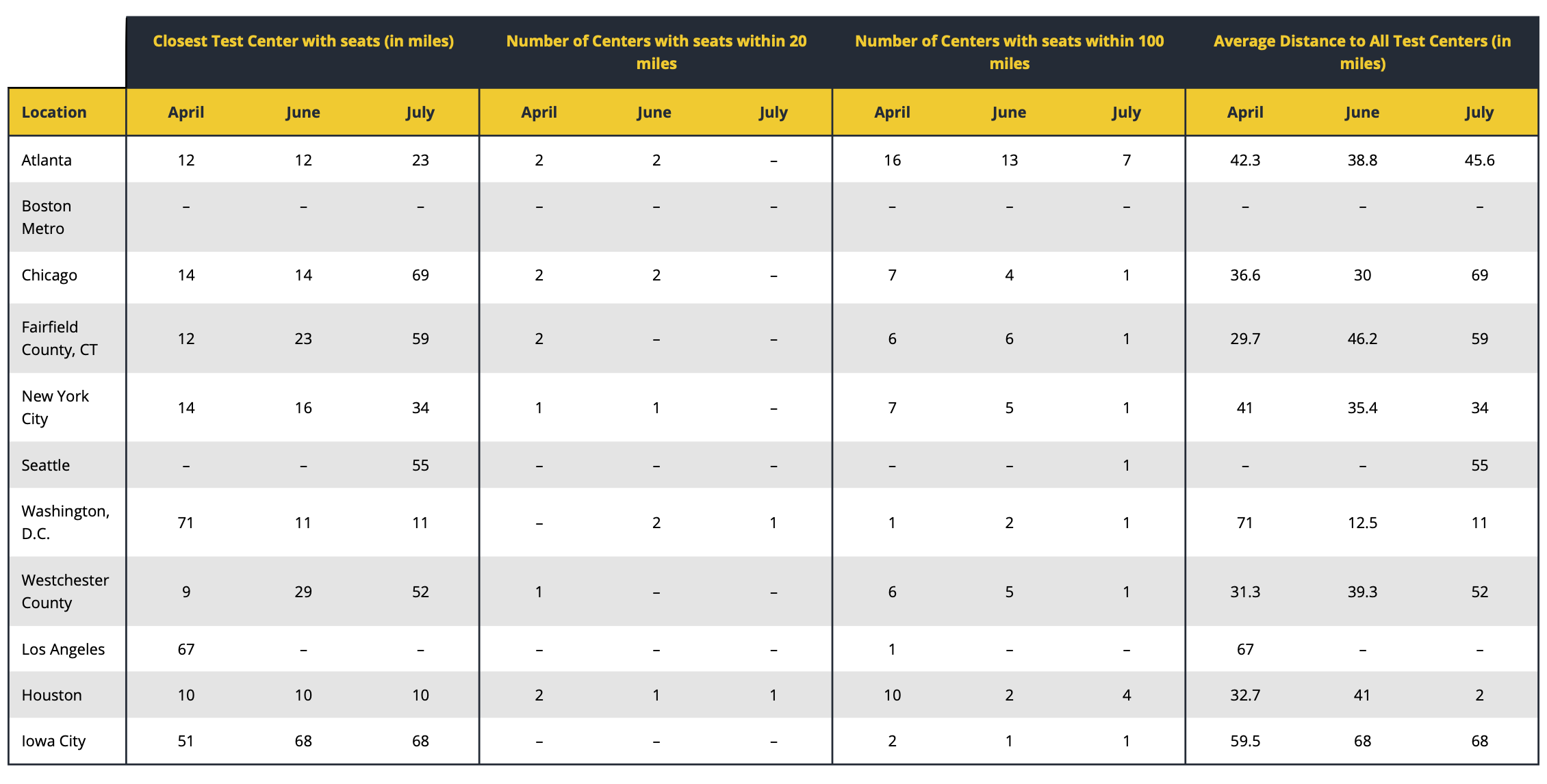

Registration is officially open for the April, June, and July tests. Test availability varies greatly depending on where a student lives. As of 1/9/2025, here is the availability for testing for students in various geographic areas:

For students living in Atlanta, Chicago, New York, and Houston, ACT testing is readily available in April. For students living in LA, DC, Seattle, or Boston, testing options are much harder to come by if not completely absent. As we move to the June and July tests, fewer test centers have committed to offering the digital ACT, but this will most likely change as we get deeper into the new year. Access is uneven, and the ACT has some work to do to make this test available in all markets.

When it comes to taking the optional Science section, we currently recommend it. We do not know how individual colleges will respond to the ACT’s changes, and we never want our students to be caught needing the Science section for a particular school after their testing is behind them. To be conservative, until there is more information about whether schools will require the optional Science section, you should plan to take it. Also, contact the school admission offices where you’re applying to check their requirements.

While a shorter ACT with fewer items and more time per question is undeniably student-friendly, the ACT has yet to demonstrate its ability to successfully administer these tests in a digital format at scale. There were, in fact, numerous technical issues when the ACT converted all international testing to a digital format in 2019. The US market for ACT testing is much larger than the international market, which would only put more strain on digital administration.

While we are big fans of the new shorter format and more generous timing of the Core ACT, we want to ensure that the rollout goes smoothly for our students before strongly recommending the shift to digital testing. The decision to move to the shorter digital format in April, June, or July or wait for the paper version in September is one that students must make individually.